The previous two posts in this serious dealt with what would happen if Canada’s electoral votes were added to the United States. This post will examine what would happen if the same occurred with Mexico.

A note to all Mexican readers: this post was written for serious political analysis along with it. It is not meant to offend, and sincere apologies are offered if any offense at all is taken.

More below.

Mexico is a lot bigger than Canada. Canada has a population of 34 million; Mexico has a population of 112 million. Indeed, it’s one of the most populous countries in the world. The effect of adding Mexico to the United States would have far more of an impact than adding Canada.

One can calculate the number of electoral votes Mexico has this way. The first post in this series noted that:

A state’s electoral vote is based off the number of representatives and senators it has in Congress. For instance, California has 53 representatives and 2 senators, making for 55 electoral votes.

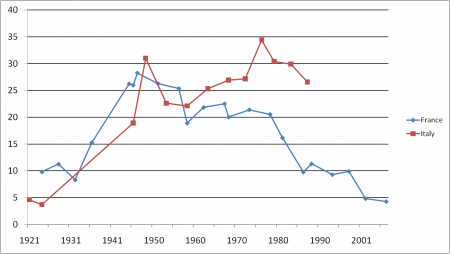

The United States Census estimates its population at approximately 308,745,538 individuals. The House of Representatives has 435 individuals, each of whom represents – on average – approximately 709,760 people. If Canada was part of the United States, this would imply Canada adding 48 (rounding down from 48.47) representatives in the House.

This is a simplified version of things; the process of apportionment is quite actually somewhat more complicated than this. But at most Canada would have a couple more or less representatives than this. It would also have two senators, adding two more electoral votes to its 48 representatives.

Mexico’s population in 2010 was found to be exactly 112,322,757 individuals. Using the same estimates as above, one would estimate Mexico to have 158.25 House representatives. Adding the two senators, one gets about 160 electoral votes in total:

This is obviously a lot of votes. For the sake of simplification let’s also not consider Mexico’s powerful political parties in this hypothetical.

How would Mexico vote?

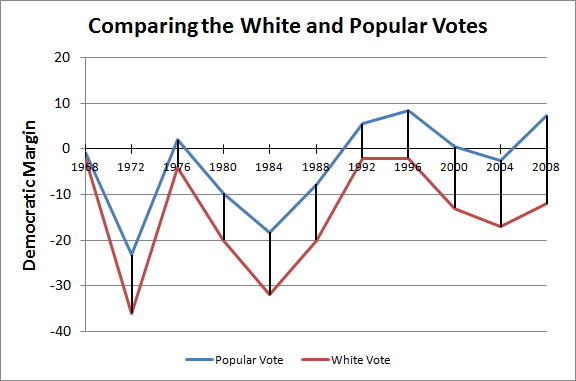

Well, it would probably go for the Democratic Party (funny how that tends to happen in these scenarios). This is not something many people would disagree with. Most Mexican-Americans tend vote Democratic. The Democratic platform of helping the poor would probably be well-received by Mexicans, who are poorer than Americans. Moreover, the Republican emphasis on deporting illegals (often an euphemism for Mexican immigrants, although some Republicans make things clearer by just stating something like “kick out the Mexicans”) would probably not go well in Mexico.

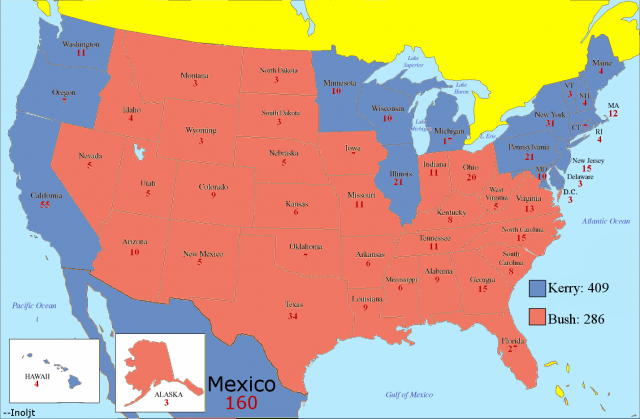

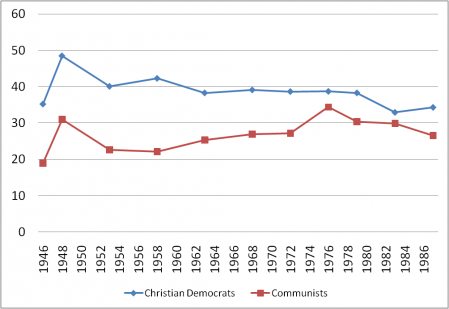

Here’s what would happen in the 2004 presidential election, which President George W. Bush won:

Senator John Kerry wins a pretty clear victory in the electoral vote. He gains 409 electoral votes to Mr. Bush’s 286 and is easily elected president.

What states would Mr. Bush need to flip to win?

In the previous post, where Canada was added to the United States, Mr. Bush would merely have needed to flip one: Wisconsin. Given his 0.4% loss in the state, this would require convincing only 6,000 voters to switch.

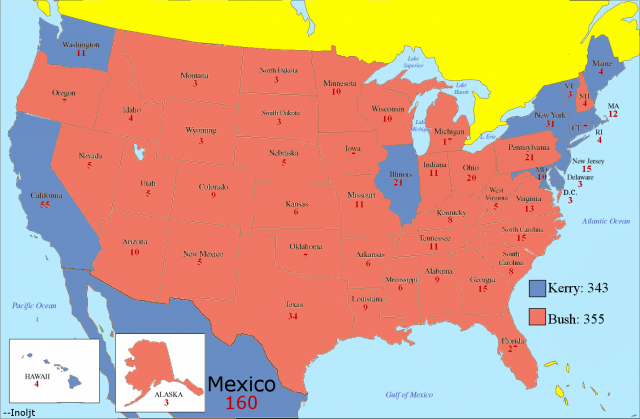

Mexico is a lot harder. In order to win, Mr. Bush needs to shift the national vote 4.2% more Republican. This flips six states: Wisconsin, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Minnesota, and finally Oregon (which he lost by 4.2%). They go in order of the margin of Mr. Bush’s defeat to Mr. Kerry:

But there’s a caveat here: in this scenario the entirety of Mexico is assumed to only have two senators. The fifty states have 435 representatives and 100 senators, making for 535 electoral votes in total (plus Washington D.C.’s three). Mexico, on the other hand, has 158 representatives and two senators, making for only 160 electoral votes. Obviously, Mexico’s influence is strongly diluted.

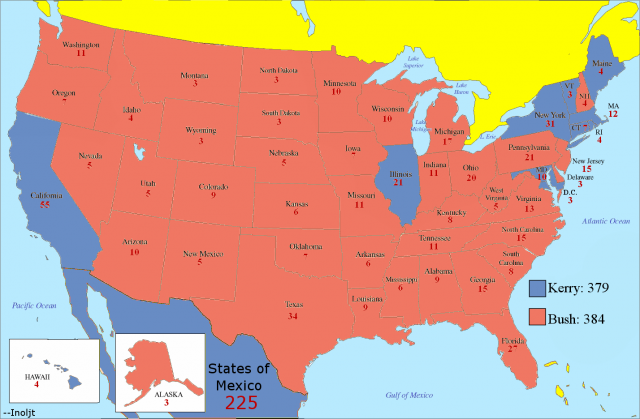

Mexico itself is organized into 31 states and one federal district. Assume that instead of the entire country voting as one unit, Mexico is divided in the electoral college into these districts. Each Mexican state (and Mexico City) would receive two senators, giving Mexico 222 electoral votes instead of 160.

But that’s not all. There are several states in America – Wyoming, for instance – whose influence is magnified due to their low population. The “Wyomings” of Mexico are Baja California Sur, Colima, and Compeche – which each have less than a million residents. Overall, this would probably add three more electoral votes to Mexico.

This means that Mr. Bush has to flip three more states to win:

New Jersey, Washington, and Delaware go Republican under this scenario. To do this, Mr. Bush would have to shift the national vote 7.59% more Republican (the margin by which he lost Delaware).

One can see that Mexico has a far more powerful effect than Canada; a double-digit Republican landslide has turned into a tie here. That’s what happens when one adds a country of more than one hundred million individuals.

Before Democrats start celebrating however, one should note that this the hypothetical to this point has been in no way realistic. It assumes that the residents of America will not alter their voting habits in response to an extremely fundamental change.

The next post explores some conclusions about what the typical election would look like if the United States became part of Mexico.

–Inoljt