By: Inoljt, http://mypolitikal.com/

Switzerland’s landslide vote to ban Muslim minarets surprised many pundits and commentators, more familiar with the nation’s image as a bastion of tolerance and European enlightenment.

These results, in fact, are not so surprising. They derive from the peculiar structure of Swiss democracy, which effectively creates a voter base less diverse than the general public. These voters are generally predisposed to support such initiatives as the minaret vote.

I am specifically talking about Swiss citizenship. Becoming a Swiss citizen implies that one has become part of the Swiss people, and the Swiss have a very strict definitions of what this means. Since – of course – only citizens may vote, this strictness directly impacts the Swiss electorate.

While Switzerland may have an image as a tolerant place, its naturalization policy is one of the least tolerant in the Western world.

More below.

Achieving citizenship can be nearly impossible. Some communities routinely reject applicants connected in any manner to Africa or the Balkans, even if have they lived in Switzerland their whole lives. Many applicants must appear before a local citizenship committee, which asks deep-probing questions such as whether the applicant “can imagine marrying a Swiss boy,” or if said applicant likes Swiss music.

As a result, 21.9% of the Swiss population is foreign – one of the highest rates in the world. An aspiring immigrant may move to Switzerland, but neither he, nor his children, nor even his grandchildren will be guaranteed citizenship. Nearly 90% of Swiss Muslims face this situation, foreigners in a land some have lived their entire lives in.

Because Swiss immigrants are denied citizenship, they naturally cannot vote: only the Swiss people can. It is no wonder then, that Switzerland’s selectively chosen electorate regularly passes initiatives like the minaret law. Or that the anti-immigrant Swiss People’s Party won the most seats in the 2007 federal elections.

This is not to say that the Swiss people are particularly intolerant or bigoted. It is a naturally human tendency to be suspicious of outsiders. Nativist sentiments exist throughout the world, whether in English disdain for Eastern Europeans, Japanese dislike of white gaijins, Muslim discrimination against black Africans, or Russian pogroms against Jews.

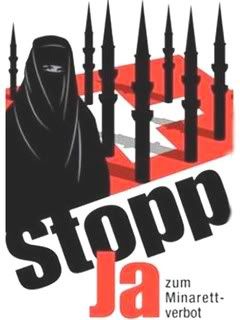

The problem is that, by restricting citizenship (and therefore the ballot) to only certain groups, Switzerland’s peculiar system encourages this inherently human flaw. Switzerland is not the only country with xenophobic sentiment; many Americans, for example despise Spanish-speaking Latinos. But in the United States, these Latinos (or their children) can vote; in Switzerland 90% of Muslims can’t vote, because they are denied citizenship. That is why the Swiss People’s Party can run an ad like this:

The Swiss People’s Party won that referendum. Republicans, on the other hand, wish to appeal to the Latino electorate; very few would dare do such a thing.

If Switzerland is to prevent more minaret initiatives from passing, it should make naturalization easier – at the very least, for example, it could grant citizenship to third-generation citizens. In doing so, Switzerland can follow America’s lead, a country whose naturalization policy is among the most progressive in the world. America is also the world’s superpower. That is not a coincidence.