When we look at large amounts of data, it’s hard to grasp all the relationships just from numbers. If we just have lots of subjects but not a lot of variables there are some fairly common graphs to help show the data (see graphics: the good, the bad, and the ugly for some methods).

But if we have a lot of variables, as well, then even those plots aren’t a complete solution. One attempt to model data like this, with lots of subjects and lots of variables, is the biplot. More below the fold

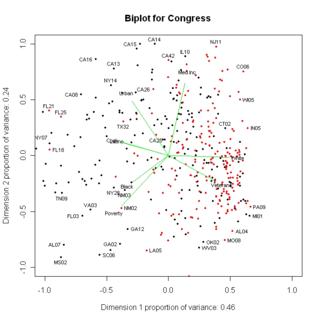

There are various types of biplots; we’re only going to be talking about the most common kind: The principal component biplot. There are a few steps to making one of these. You can get all math-y, but I’m not going to. I’ll try to keep it as simple as possible, but if you hate math, and want to get to the politics…. well, look at the figure and then skip down to where I have the phrase “Interpreting the biplot”

This type of biplot works with variables that are continuous, or nearly so. That is, variables that can take on any value, not just a few. Things like weight, height, and so on, rather than things like religion, or hair color, that can only take certain values.

I had data on various demographic aspects of each of 435 congressional districts:

% White non-Latino, % Black non-Latino, % Latino, % other

Median income, % in poverty

% Rural

% Veterans

Cook PVI

and whether the Rep was a Democrat or Republican

Except for the last, all these are continuous, or nearly so. I changed Cook PVI a little, giving negative values to those that were R and positive to those that were D.

How can we represent all these data on one graph:

(it’s a little bigger here )

wow…. what’s that?

Well, the first thing I did was a principal components analysis (PCA) . Skipping a lot of possibly important information — Get a correlation matrix of the data. The goal of PCA is to find new variables that are linear combinations of the original variables. The first PC should represent as much of the variance in the table as possible. The second PC should represent as much of the remaining variance as possible, subject to being orthogonal to the first PC (you can think of orthogonal as meaning ‘unrelated’, although that isn’t exactly right).

In the figure above, note that the x-axis (that’s the horizontal one) is labeled Dimension 1: Proportion of variance .46. That means that one variable, a linear combination of all the other variables, represents about half the variance in all those variables. In other words, if you wanted to predict all of the original variables using only one number, this new number (the PC) would account for about half the variance in all those other numbers. The y-axis (the vertical one) says that dimension 2 represents .24 of the variance. So, together, this plot represents about 70% of the variance in all the original variables.

Next, each district gets a score on each of the PCs. Those are the dots. I’ve labeled some of them (more below).

Next, each variable gets whats called a loading on the PCs (never mind the details). These are represented by lines.

Interpreting the biplot.

OK, no more math (well…. I hope not!)

How to interpret the biplot? First, note that the two proportions add to .7. This biplot leaves out a lot (more below). But it can still be useful. Next, look at the lines. For example, poverty goes to the lower left. So the variable poverty is low on PC1 and low on PC2. Both Cook and Latino are off to the left, so they are low on PC1 and moderate on PC2. White is off to the right.

The CDs in the lower left (AL07, MS02, SC06, GA02) are high on poverty and high on Black….indeed, these are all “Black districts”. The ones all the way on the left (NY07, FL18, 21, 25) are highly Latino districts, that aren’t Republican (more later). The ones on the lower right have a lot of veterans. And so on.

Now, we can use this biplot to find districts that might be vulnerable. When there’s a black dot (Democratic rep) in a sea of red dots (Republicans) or vice versa, that might be a seat that’s vulnerable.

Vulnerable Republican seats include FL18, FL21, FL25, CA42, NM02, CA25, CA21 (that’s the red dot near NY28).

Looking at the data you have presented in your series, a lot of points just seem to come together. In no particular order, these include:

Democratic seats include many with incredibly high PVI ratings. The most Democratic district had a PVI of D+43 and the tenth most Democratic had a PVI of D+36. This was noticeably higher than the PVI of the most Republican district in the country, UT-3 (R+26). The tenth most Republican district had a PVI of R+20 (KS-1, TX-8).

By a hand count using your data, 46 seats had a Democratic representative in Congress and a Republican PVI. In contrast, only 10 seats had a Republican in Congress and a Democratic PVI. Fully 22 of these seats with a Democrat and a Republican leaning district had a PVI of R+6 or greater; Delaware At Large (which you list as D+5.4) has the biggest Democratic lean of any Republican seat.

At least five Democrats represented seats with a PVI of R+10 or higher: Chet Edwards (R+18), Jim Matheson (R+17)Gene Taylor (R+16),Nick Lampson (R+15), and Ike Skelton (R+11). No figures were given but the two Dakota Dems, Earl Pomeroy and Stephanie Herseth Sandlin, may very well fall into those categories.

Given these numbers, I figured that the PVI was a not particularly valuable instrument when it came to predicting vulnerable Republican seats in 2006. That proved to be wrong as Republicans who had racked up 60% + against weak opposition in D friendly districts either fell or got very sharp challenges.

OTOH, Republican attempts to use the PVIs as a targeting device against Democrats in the House who might be picked off proved spectacularly unsuccessful People like Spratt, Pomeroy, Herseth Sandlin and Moore of Kansas all made the Republican and prognosticator lists and really had easy times for the most part.

Compare the Presidential numbers and the local rep often runs five to ten points ahead of the national ticket. Gene Taylor, who must be a force of nature or something, ran about 50 points ahead of Kerry’s numbers in his district in 2006.

Are Democratic House candidates that good or do Democrats, specifically Kerry, underperform at the national level. I suspect, a bit of both. The ability of Republican operatives to portray a spoiled, prep school and Ivy League failure like George W. Bush as an Everyman and to picture Al Gore (who served in Nam and actually held a real job once) as an elitist snob is stunning. The ability to portray Georgie who actually has a terrible temper as a sweet patriotic minded good old guy while McCain is Mr. Temper Tantrum and Democrats ahave problems, too is stunning. Cut through the crap and we are probably leaving at least five points on the table in a national race (the last two anyway). Guess we should get Bill Clinton type results every four years with 370+ electoral votes.

Now, how do you pick up the difference in Republican House performance on your map? The swirl of dots should automatically correlate to what is and not what Charlie Cook’s unitary number shows. Way to go. (And you thought I’s never come back to the subject).