By: Inoljt, http://mypolitikal.com/

The country Poland is comprised of two main political parties; the first is Prawo i Sprawiedliwosc (PiS) – “Law and Justice” in English. This party is a populist group which runs upon anti-corruption and anti-Communist credentials. The second party is the Platforma Obywatelska (PO) – in English the “Civic Platform” – a group espousing support for free market capitalism.

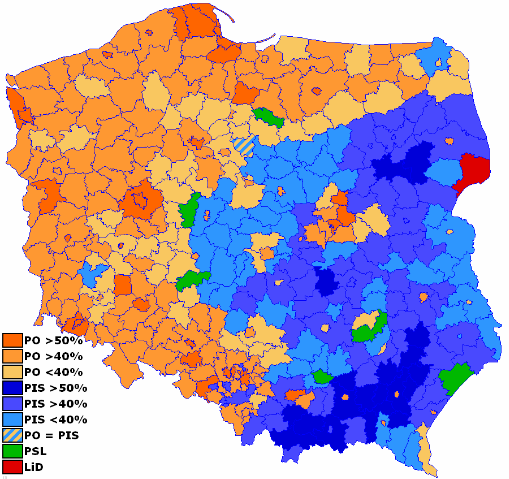

On October 2007, Poland held parliamentary elections between the two parties. Most of the Western media backed the Civic Platform (PO), disliking the unpredictability of the Kaczynski twins (leaders of Law and Justice). Here is a map of the results:

More below.

As it turns out, the Civic Platform (PO) won the election, taking 41.5% of the vote. Law and Justice polled 32.1%, with the rest of the vote going to third parties.

A clear regional split is apparent in these results. Poland’s southeast – with the exception of Warsaw – generally voted for Law and Justice (PiS). On the other hand, support for the Civic Platform (PO) took a sickle-like shape along Poland’s northern and western borders.

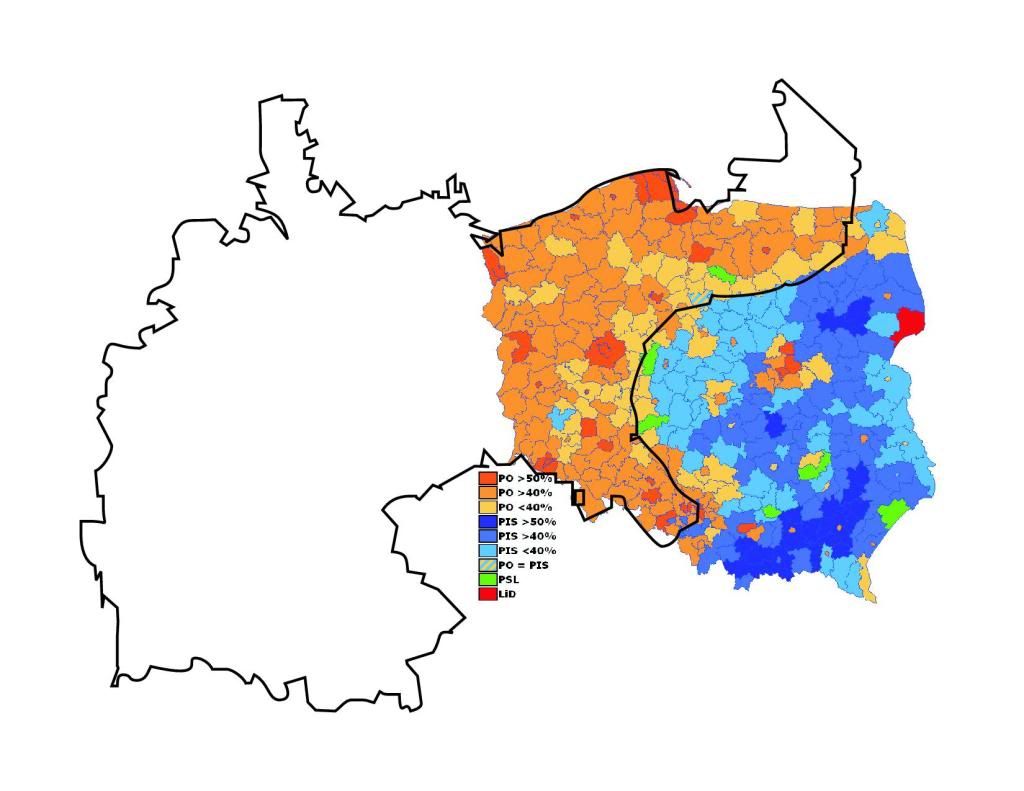

These patterns are not random. Take a look at pre-WWI Imperial Germany superimposed upon this map:

As the map above indicates, there is a powerful correlation between the borders of Imperial Germany and support for the free-market, pro-Western Civic Platform (PO) Party. In contrast, areas that voted strongest for Law and Justice (PiS) used to belong to the Austrian-Hungarian and Russian empires.

An exact map of Poland’s pre-WWI boundaries looks as so:

These voting patterns have very little to do with any actual German presence in pro-Civic Platform regions. Few Germans live in the regions that used to belong to Imperial Germany; after WWII the process of ethnic cleansing effectively expelled them all from modern-day Poland.

The reason, rather, involves economics. The German Empire was far more economically developed than the Russian and Austria-Hungarian empires. This legacy is still present today, as Poland’s 2007 parliamentary elections showed quite starkly.

An interesting instance of Poland’s “German” divide occurred during the 1989 parliamentary elections. One may recognize this date: it was the year that communism fell in Poland. In these elections the Polish communists actually competed directly with the anti-communist Solidarity movement.

Here are the results:

Solidarity, of course, won in a landslide victory – which is why communism fell in Poland. Yet even in these elections one can make out the regional, east-west divide in Poland. Surprisingly, the more “Western” and economically developed regions actually gave stronger support to the Communists.

All in all, Poland’s electoral divide provides a powerful example of how long-past history can influence even the most modern events. Whatever the political parties of Poland’s future, and whatever their political positions, one can be fairly sure that Polish elections will continue to replicate the boundaries of pre-WWI Germany for a long, long time.