This is the second part of two posts analyzing Ukrainian elections. This second part will focus upon many factors that lead to Ukraine’s exceptional regional polarization. The first part can be found here.

Two Ukraines

Modern Ukraine is a strange hybrid of two quite different regions. One part, composed of western and central Ukraine, is politically more aligned with the West; it favors, for instance, joining the European Union. This part includes the capital Kiev. The other part of Ukraine, consisting of the Black Sea coast and eastern Ukraine, remains more loyal to Russia and the memory of the Soviet Union. It includes Donetsk Oblast (formerly named Stalino Oblast), the most populous province in the country.

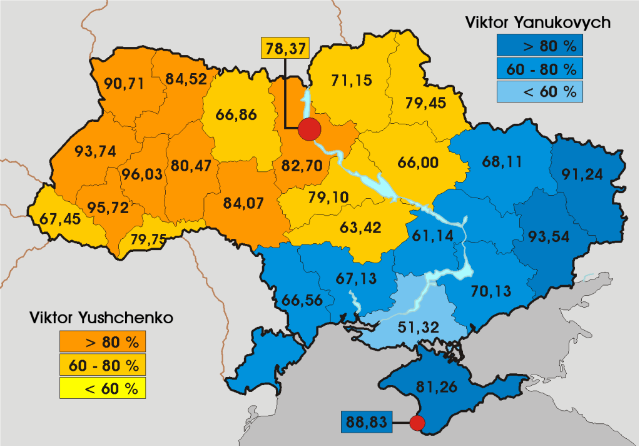

This division is reflected in Ukrainian politics. Take the 2004 presidential election, in which pro-Western candidate Viktor Yushchenko faced off against pro-Russian candidate Viktor Yanukovych:

More below.

Few things better illustrate the boundary between east and west Ukraine than this election, which Mr. Yushchenko ended up winning by a seven-point margin.

These divisions have long-standing roots. During the 16th and 17th centuries, for instance, much of Ukraine was under the control of the Poland-Lithuania. This country, which at one point constituted the largest nation in Europe, declined in the 18th century and was eventually partitioned by its stronger neighbors Prussia, Russia, and Austria.

Here is a map of Poland-Lithuania at its peak:

As the map makes clear, there is a strong correlation between the parts of Ukraine once controlled by Poland-Lithuania and the parts of Ukraine that today vote for pro-Westerners such as Mr. Yushchenko. Although Poland-Lithuania is long gone, the vestiges of Polish influence still exist in these places, drawing western and central Ukraine closer to the West than eastern Ukraine and the Black Sea region.

These two parts of Ukraine differ in another, even more important aspect: language. Take a look at the most Russian-speaking regions of Ukraine:

The correlation between the percentage of Russian speakers and the vote for pro-Russian candidate Viktor Yanukovych is even stronger here. The three provinces with more than 60% of Russian-speakers gave Mr. Yanukovych’s his strongest support; Mr. Yanukovych managed to gain greater than 80% of the vote in each of them, despite losing the overall vote by 7%.

Language was a matter directly related to the Soviet Union. While on paper all languages were equal in the Soviet Union, in reality there was little question that speaking Russian was necessary to succeed. Today the situation is the opposite; the government encourages individuals to speak Ukrainian, although many in the country use Russian.

Ironically, Mr. Yanukovych himself is a native-born Russian-speaker. According to the Kiev Post, his Ukrainian remains imperfect to this day. The current president is reported to desire adding Russian to Ukraine’s list of official languages (which at the moment includes solely Ukrainian). This would be quite controversial if actually done.

Ukraine’s Future

Polarization, like that illustrated in the humorous picture above, is a disturbing phenomenon for any country. In Ukraine’s 2004 presidential election, all but one province gave more than 60% of the vote to a single candidate. This is the type of political division that sometimes leads to civil war, such as which occurred in Yugoslavia. That is one possible path for Ukraine to follow, unlikely as it may seem at the moment.

Yet polarization of this sort does not necessarily lead to separation. In the 2010 presidential election, polarization declined slightly; as memories fade, this trend may continue. And fortunately for Ukraine, the East-West division does not extend to ethnicity; Russian-speakers and Ukrainian-speakers may have a different language, but they look the same. It is a sad comment on the human condition that this makes a break-up of Ukraine less likely.

Moreover, a number of other countries contain similar electoral divisions without splitting up. Former East Germany votes quite differently from former West Germany (especially with regards to the Left Party, the ex-communist party), but Germany certainly will not break-up into pieces anytime soon. After the Civil War, the South unanimously supported one party for decades – parts of it still do, if one excludes blacks – but the idea of another national schism is unthinkable today. If things go well for Ukraine, the electoral divide in its voting patterns may remain nothing more than that.

–Inoljt, http://mypolitikal.com/