This is the first part of two posts analyzing patterns in the 2010 Senate midterm elections. The second part can be found here.

The 2010 congressional midterm elections constituted, by and large, a victory for the Republican Party. In the Senate Republicans gained six seats. While this was somewhat below expectations, it was much better than Republican hopes just after 2008 – when many expected the party to actually lose seats.

The Senate results provide some interesting fodder for analysis. The table below indicates which Republicans Senate candidates did the worst in 2008. It does so by taking the Republican margin of victory or defeat in a given state and subtracting this by the Cook PVI of the state (the Cook PVI is how a state would be expected to vote in a presidential election in the event of an exact tie nationwide). Given that Republicans won the nationwide vote this year, the average Republican candidate would be expected to do better than the state’s PVI. A bad Republican candidate would actually do worse than the state’s PVI.

Let’s take a look at this table below the flip.

| State | Republican Margin | Cook PVI | Republican Overperformance |

| South Dakota | 100.00% | 8.9% | 91.10% |

| North Dakota | 53.91% | 10.4% | 43.51% |

| Kansas | 43.72% | 11.5% | 32.22% |

| Iowa | 31.05% | -1.0% | 32.05% |

| Idaho | 46.25% | 17.4% | 28.85% |

| Oklahoma | 44.50% | 16.9% | 27.60% |

| Florida | 28.69% | 1.8% | 26.89% |

| South Carolina | 33.83% | 7.8% | 26.03% |

| New Hampshire | 23.22% | -1.6% | 24.82% |

| Arizona | 24.14% | 6.1% | 18.04% |

| Alabama | 30.47% | 13.2% | 17.27% |

| Ohio | 17.44% | 0.7% | 16.74% |

| Georgia | 19.31% | 6.8% | 12.51% |

| Arkansas | 20.96% | 8.8% | 12.16% |

| Missouri | 13.60% | 3.1% | 10.50% |

| Illinois | 1.60% | -7.7% | 9.30% |

| Louisiana | 18.88% | 9.7% | 9.18% |

| Utah | 28.79% | 20.2% | 8.59% |

| Indiana | 14.58% | 6.2% | 8.38% |

| North Carolina | 11.77% | 4.3% | 7.47% |

| Wisconsin | 4.84% | -2.4% | 7.24% |

| Pennsylvania | 2.02% | -2.0% | 4.02% |

| Kentucky | 11.47% | 10.4% | 1.07% |

| Washington | -4.73% | -5.0% | 0.27% |

| Alaska | 11.94% | 13.4% | -1.46% |

| Colorado | -1.63% | 0.2% | -1.83% |

| California | -10.01% | -7.4% | -2.61% |

| Nevada | -5.74% | -1.3% | -4.44% |

| Connecticut | -11.94% | -7.1% | -4.84% |

| Delaware | -16.58% | -7.0% | -9.58% |

| Oregon | -17.98% | -4.0% | -13.98% |

| New York (S) | -27.84% | -10.2% | -17.64% |

| Maryland | -26.44% | -8.5% | -17.94% |

| West Virginia | -10.07% | 7.9% | -17.97% |

| Vermont | -33.41% | -13.4% | -20.01% |

| New York | -34.10% | -10.2% | -23.90% |

| Hawaii | -53.24% | -12.5% | -40.74% |

| Total/Average | 5.54% | 2.3% | 8.08% |

(Note: The data in Alaska and Florida refer to the official candidates nominated by the parties, not the independent candidates – Senator Lisa Murkowski and Governor Charlie Crist – who ran in the respective states).

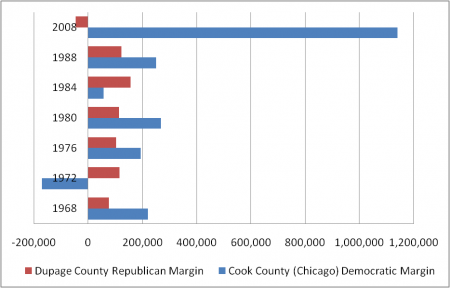

This table reveals some fascinating trends. There is a very clear pattern: the worst Republican candidates ran in the bluest states – and the bluer the state, the more the Republican underperformed. This does not just mean that these Republicans lost, but that they lost by more than the average Republican was supposed to in the state. Republican candidates did worse than the state’s PVI in thirteen states; nine of these states had a Democratic PVI.

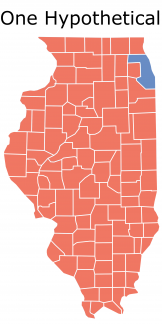

There seems to be a PVI tipping point at which Republicans start underperforming: when a state is more than 5% Democratic than the nation (PVI D+5). Only one Republican in the nine states that fit this category overperformed the state PVI (Senator Mark Kirk of Illinois ).

Something is puzzling about this pattern. It is true that states like Connecticut or Maryland will probably vote Democratic even in Republican victories. The Cook PVI predicts that Democrats will win by X% in the event of a national tie in the popular vote. One would thus have expected Republican candidates to do better than this in 2010, given that 2010 was the strongest Republican performance in a generation.

Yet this did not happen. In a lot of blue states Democrats actually did better than the Cook PVI would project them to do – that is, said blue states behaved like the Democrats had actually won the popular vote, which they certainly did not in 2010. The bluer the state, the stronger this pattern.

There are a couple of reasons why this might be. The first thing that comes to mind is the money and recruiting game. The Republican Party, reasonably enough, does not expect its candidates to win in places like New York and Maryland . So it puts less effort into Republican candidates in those states. They get less money – and therefore less advertising, less ground game, and so on. Nobody had any idea who the Republican candidate in Vermont was, for instance. That probably contributes to Republican underperformance in deep-blue states.

The second factor might be a flaw in the model the table uses. Democratic and Republican strongholds, for whatever reason, behave differently from “uniform swing” models. In almost all the counties President Barack Obama won, for instance, he improved upon President Bill Clinton 1992 and 1996 performance – despite the fact that Mr. Clinton won by similar margins in the popular vote. This holds true from San Francisco to rural Mississippi . In the 2010 Massachusetts special Senate election, the most Democratic areas of Massachusetts swung least towards Republican Senator Scott Brown. The fact that the worst Republican candidates ran in the bluest states fits the pattern.

The table presents another startling pattern, which will be discussed in the next post: there are surprisingly few Republicans who did worse than they were supposed to in red states.

–Inoljt