On April 5th, 2011 Wisconsin held an election to choose a Wisconsin Supreme Court nominee. The supposedly non-partisan election turned into a referendum on Republican Governor Scott Walker’s controversial policies against unions. Mr. Walker’s new law will probably be headed to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, and since the Supreme Court is elected by the voters Democrats saw one last chance to defeat his law.

The frontrunner was the incumbent justice, Republican David Prosser. The Democratic favorite was relatively unknown JoAnne Kloppenburg. The two candidates essentially tied each other, although Mr. Prosser has taken the lead following the discovery of 14,315 votes in a strongly Republican city.

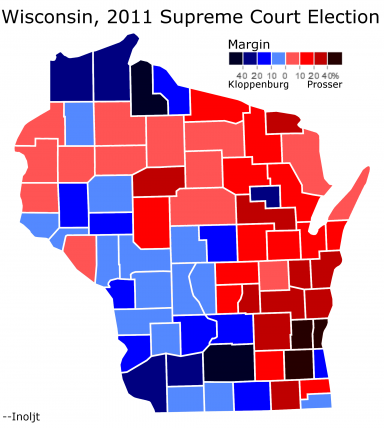

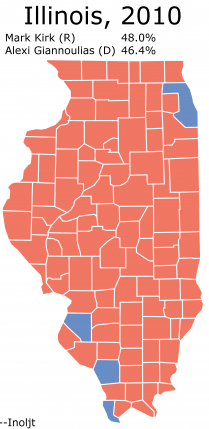

Here are the results of the election:

More below.

For a supposedly non-partisan election, the counties that Mr. Prosser won were almost identical to the counties that Republicans win in close races. There was essentially no difference.

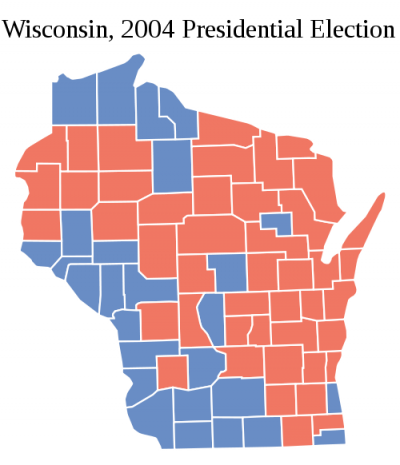

A good illustration of this similarity is provided by comparing the results to those of the 2004 presidential election in Wisconsin. In that election Senator John Kerry beat President George W. Bush by less than 12,000 votes:

It is pretty clear that this non-partisan election became a very partisan battle between Democrats and Republicans.

Nevertheless, there were several differences between this election and the 2004 presidential election.

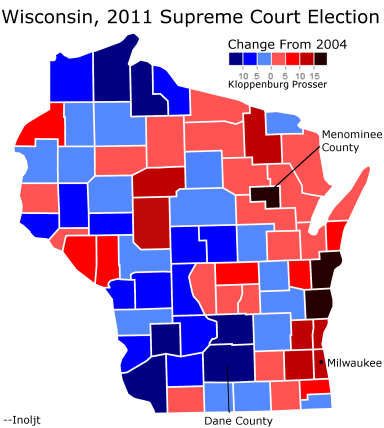

Here is a map of how Mr. Prosser did compared to Mr. Bush:

In most places Mr. Prosser is on the defence. He improves in his areas of strength by less than Ms. Kloppenburg does in her areas of strength. More Bush counties move leftward; fewer Kerry counties move rightward.

The great exception, however, is Milwaukee. In that Democratic stronghold Mr. Prosser improved by double-digits over Mr. Bush. Ms. Kloppenburg almost makes up the difference through a massive improvement in Madison (Dane County), the other Democratic stronghold, along with a respectable performance outside Milwaukee and its suburbs. But she doesn’t quite make it.

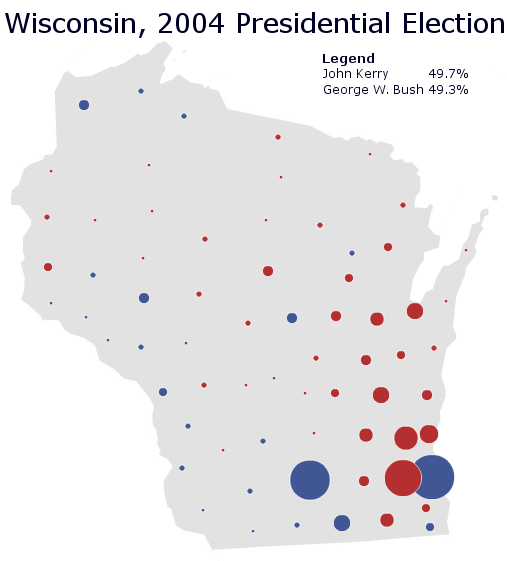

Here is a good illustration of the importance of Milwaukee:

As one can see, the two great reservoirs of Democratic votes belong in Madison and Milwaukee. Ms. Kloppenberg got all the votes she needed and more in Madison; she got far fewer than hoped for in Milwaukee.

Much of Mr. Prosser’s improvement was due to poor minority turn-out.

Milwaukee is the type of Democratic stronghold based off support from poor minorities (Madison is based off wealthy white liberals and college students). Unfortunately for Ms. Kloppenberg, minority turn-out is generally low in off-year elections such as these.

Another example of this pattern is in Menominee County, a Native American reservation that usually goes strongly Democratic. In 2011 Menominee County voted Democratic as usual (along with Milwaukee), but low turn-out enabled Mr. Prosser to strongly improve on Mr. Bush’s 2004 performance.

All in all, this election provides an interesting example of a Democratic vote depending heavily upon white liberals and the white working class (descendants of non-German European immigrants), and far less upon minorities.

–Inoljt, http://mypolitikal.com/