This is the third part of a series on Communism in Western Europe; this section focuses on Italy in particular. The previous parts can be found here.

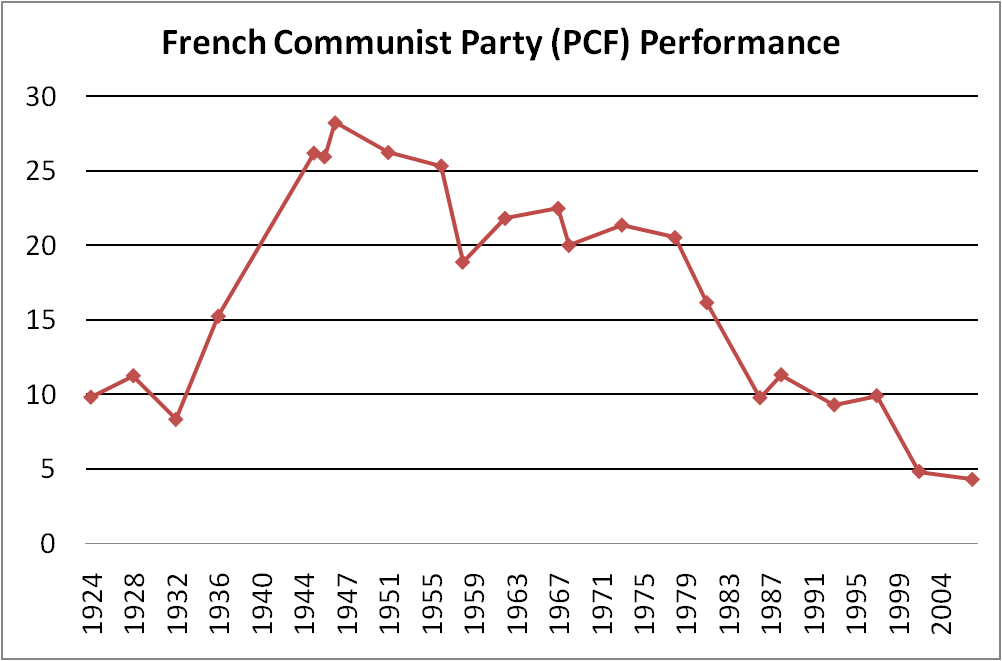

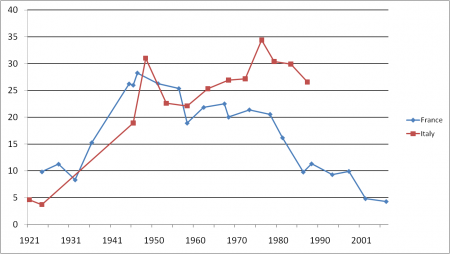

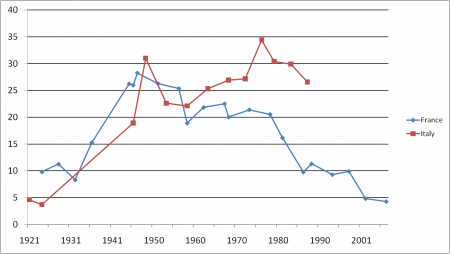

The Italian Communist Party (PCI) formed in 1921, as a break-away faction of the socialist party. In many respects, its early years were similar to those of the PCF. Like the French Communists, the Italian Communist Party (PCI) fared poorly in national elections, winning less than five percent of the popular vote. Its time to grow, moreover, was cut short by Benito Mussolini’s dictatorship; he outlawed the party in 1926.

In another parallel to their French colleagues, the Italian Communists (PCI) fought fiercely against the Nazis during WWII and won major acclaim for their efforts. After the war, the PCI took part in the new government, playing a major role in writing the new Italian constitution. As in France, however, America’s Marshall Plan curbed their influence; to gain access to U.S. aid, the Italian government kicked out the Communists. They would never again hold power in Italy.

Continued below.

Here the paths of the French and Italian Communists diverge. In France the Communist story is one of steady decline, until the PCF no longer constituted a viable political force. In Italy the story is different.

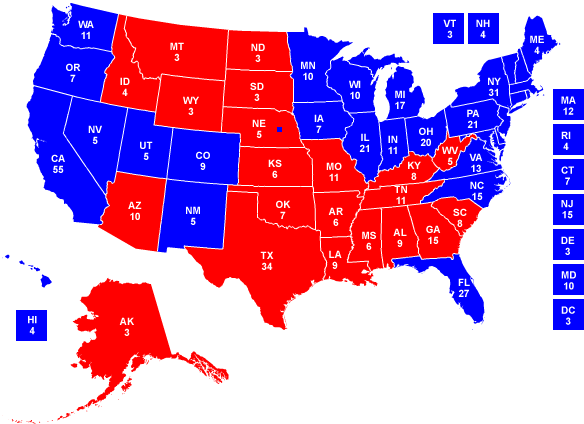

Before getting into it, however, another tale must be told – that of the 1948 general elections. This contest was the most important election in Italian history, pitting the Italian Communist Party (the PCI, allied with the socialists) against the Christian Democrats (Democrazia Cristiana, DC). It literally determined Italy’s side on the Cold War, whether it would ally with the United States or the Soviet Union. Many feared that if the Communists won, Italy would go red, never to turn back.

The election was fiercely fought; both sides were discretely funded by their respective superpowers. The Catholic Church came out strongly against the Communists (PCI), using slogans such as, “In the secrecy of the polling booth, God sees you – Stalin doesn’t.”

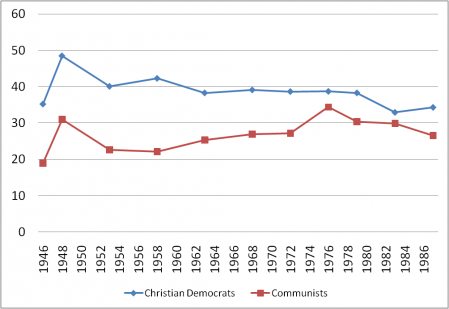

Christian Democracy (DC) blew away the Communists (PCI). While the PCI won a 31.0% vote share, their second-best performance ever, the Christian Democrats took 48.5% of the vote. Italy allied with the United States.

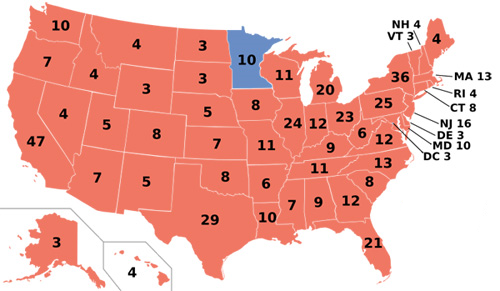

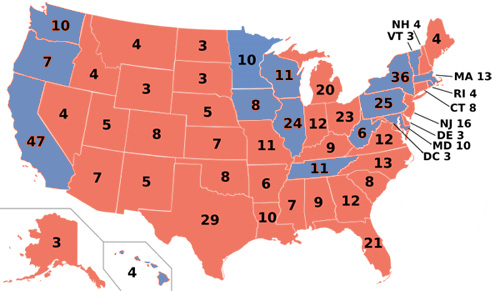

For nearly half a century thereafter, Christian Democracy governed Italy. The PCI never managed to win more votes than the Christian Democrats, although they continued to fare respectably in general elections.

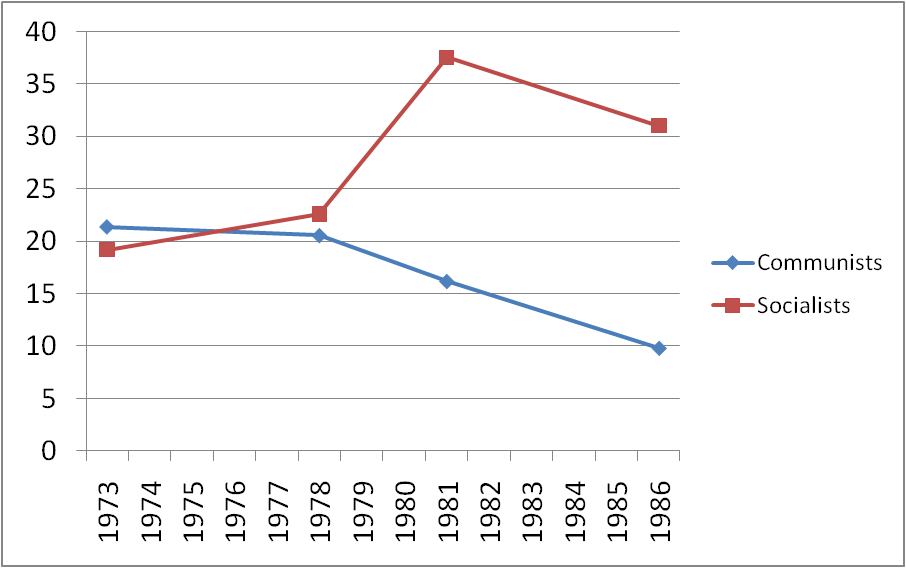

Here a crucial distinction between the French Communists and the Italian Communists occurs: while the PCF gradually declined throughout the 50s to 70s, the PCI actually strengthened itself during this era. Unlike the French Communist Party, the PCI publicly and dramatically distanced itself from the Soviet Union. Instead, the party was the most vocal advocate of eurocommunism, a far different philosophy than that espoused by the Soviet Union.

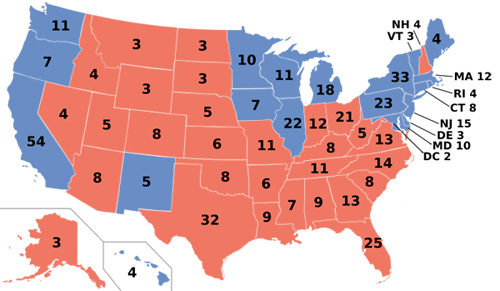

Thus, the Italian Communist Party was perceived as more acceptable and moderate than other communist parties, and its share of the vote steadily increased. In 1976, they won 34.37% of the vote, their best performance in history and a mere 4.34% behind DC. The PCI achieved this result by doing “all they could to appear as a respectable, rather conservative party committed to sensible change by constitutional means…[and] emphasise how moderate, democratic and uncorrupt they were.”

In the end, however, the PCI was still Communist, irrevocably tied to the fate of the Soviet Union no matter how distant their ties. When the USSR fell, the Italian Communist Party was broken up – though, as in eastern Europe, many parties of Italy’s left have roots from the PCI. Within a few years, DC – its reason for existence now dead – imploded under a shroud of corruption scandals.

That was the end of the old system. Today, for better or for worse, one man – Silvio Berlusconi – dominates the political arena. Yet, even with the PCI long gone, Berlusconi still invokes anti-communism to win votes. The shadow of the PCI is long indeed.

–Inoljt, http://thepolitikalblog.wordpr…