This is the fourth part of an analysis of the swing state Pennsylvania. It focuses on the industrial southwest, a once deep-blue region rapidly trending Republican. Part five can be found here.

Pittsburgh and the Southwest

Pennsylvania’s southwest has much in common with West Virginia and Southeast Ohio, the northern end of Appalachia. Electoral change in the region is best understood by grouping these three areas together as a whole.

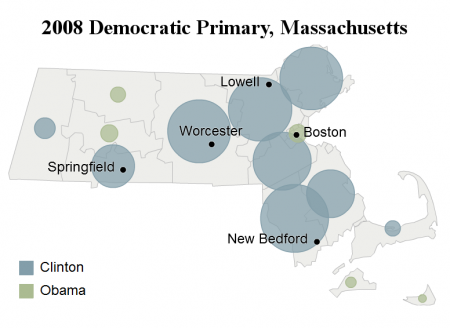

Socially conservative (the region is famously supportive of the NRA) but economically liberal, the industrial southwest voters typify white working-class Democrats. These voters can be found in unexpected places: Catholics in Rhode Island and Massachusetts, loggers along the Washington coast, rust-belt workers in Duluth, Minnesota and Buffalo, New York.

It was President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal that brought the working-class to the Democratic Party; before his time, the party constituted a regional force confined mainly to the South. In Pennsylvania, a Republican stronghold that had voted for President Herbert Hoover, Mr. Roosevelt laid the foundations for a lasting Democratic coalition.

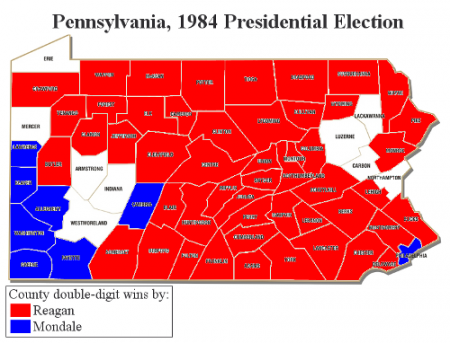

For decades, voters in southwest Pennsylvania constituted this coalition’s foundation. Take, for instance, Democratic nominee Walter Mondale:

In 1984, the industrial southwest, badly hurting from a receding recession, cast a strong ballot for Mr. Mondale. It did so again for Governor Mike Dukakis, and twice for President Bill Clinton.

Ironically, it was during the presidency of Mr. Clinton – a man much liked by Appalachia – that the Democrats became regarded as the party of the coasts and the elite. Ever since his time, Pennsylvania’s industrial southwest has been in a bad way for Democrats.

More below.

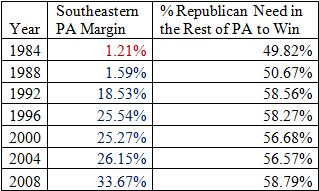

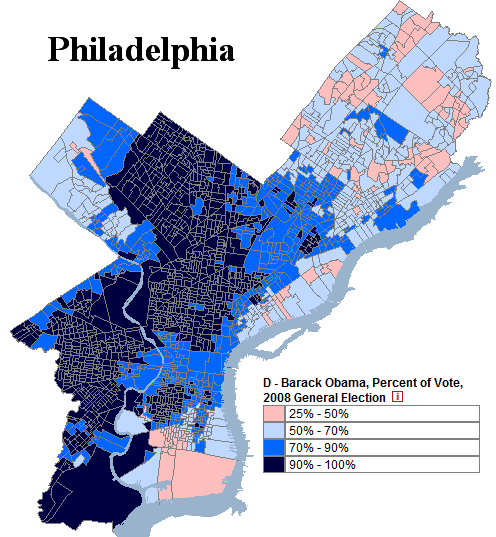

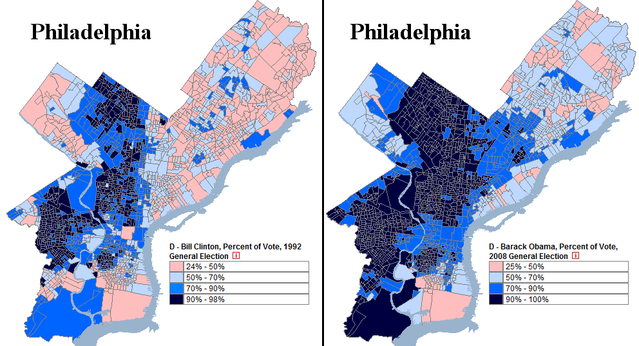

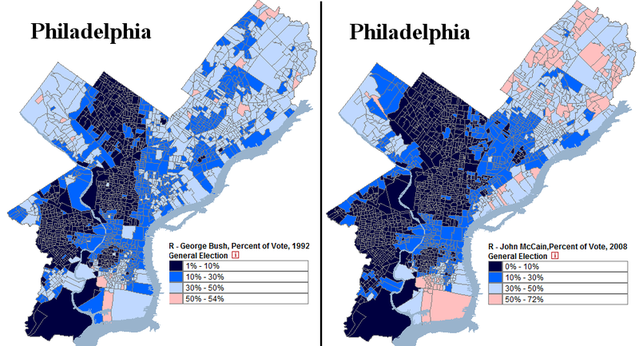

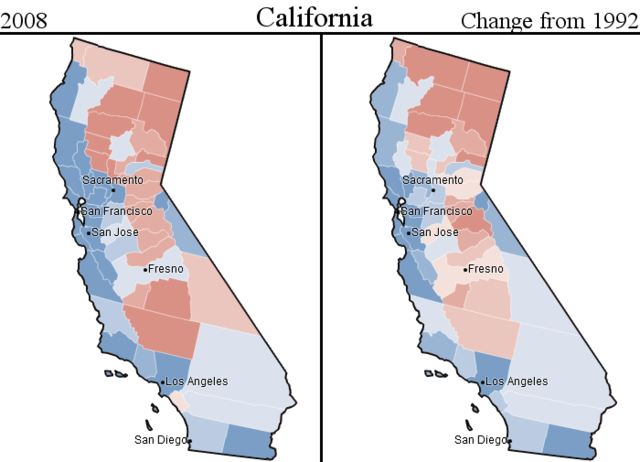

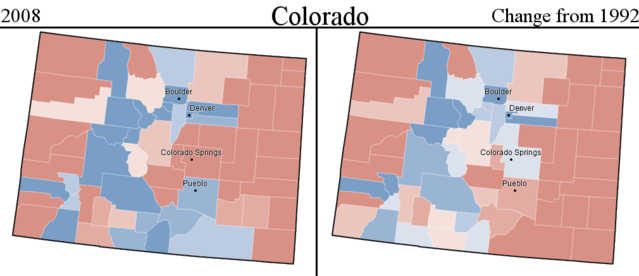

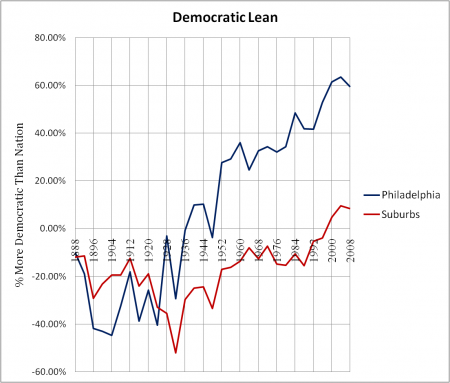

Thus, whilst metropolitan Philadelphia has been moving steadily left, Pittsburgh and the industrial southwest have been marching in the opposite direction.

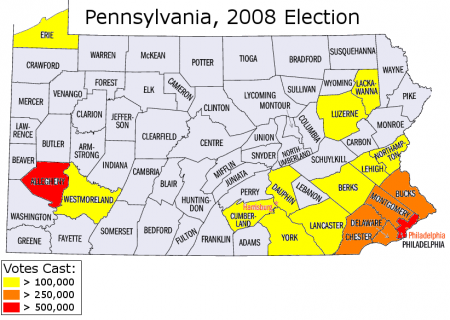

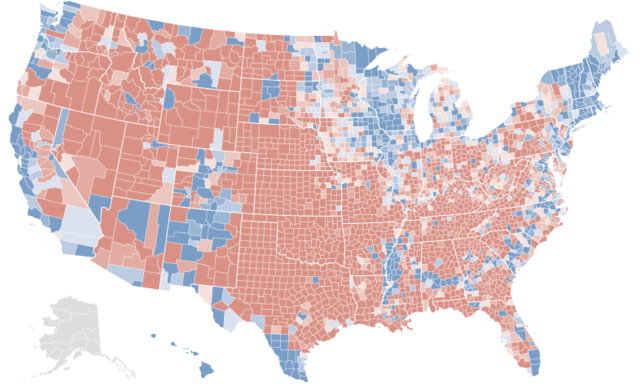

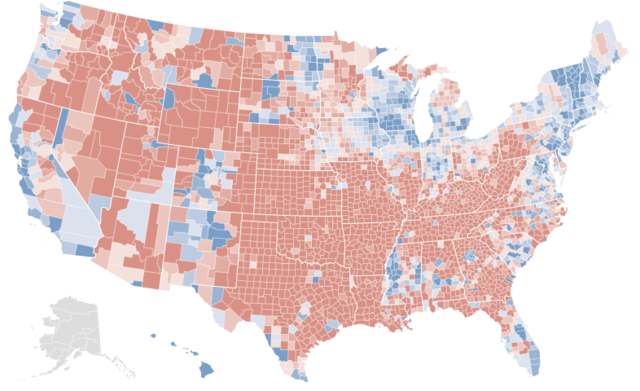

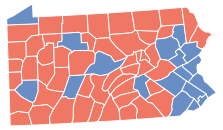

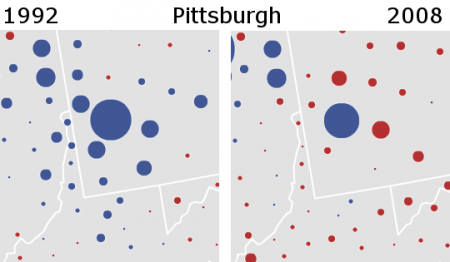

To get a sense of the movement in this region, compare these two maps:

In less than a generation’s span, one sees Democratic strength in northern Appalachia utterly vanish.

In a state where things have been going badly for Republicans, southwest Pennsylvania provides some consolation. Were it not for the southwest’s rightward trend, Pennsylvania would today be a fairly solid Democratic state.

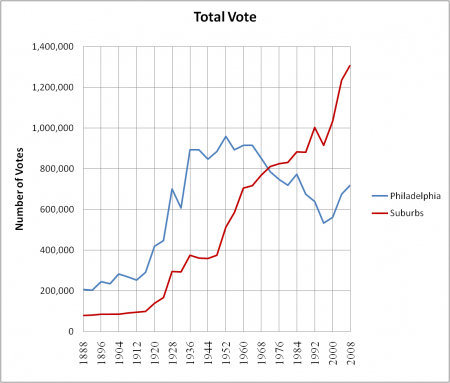

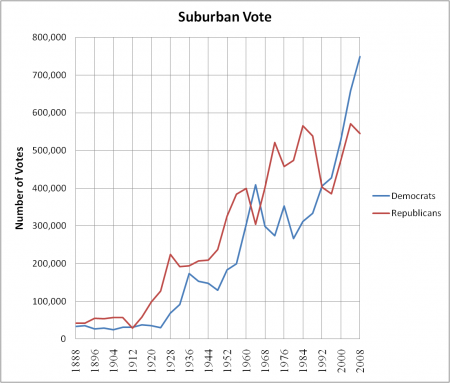

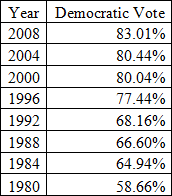

Nevertheless, if I were to choose between Pittsburgh and the industrial southwest or Philadelphia and the suburban southeast, I would much prefer the latter. While Philadelphia itself is in declining, its metropolitan area as a whole has experienced rapid growth. The southwest’s population, on the other hand, remains basically stagnant, suffering the effects of economic decline.

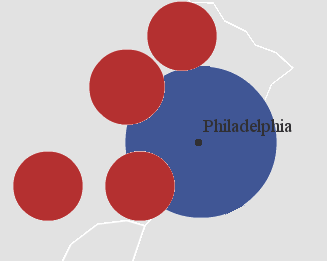

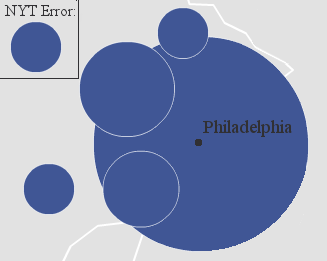

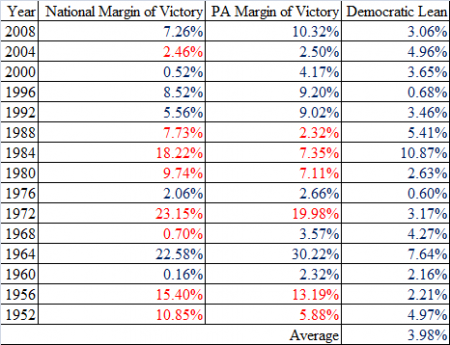

In absolute terms, moreover, eastern Pennsylvania holds far more votes:

Republicans might take comfort in Allegheny County’s vote reservoir – were it not consistently blue. Indeed, Democratic strength in Pittsburgh ensures that, as a whole, the southwest will still vote Democratic for some time yet. Although – unique to practically every other major city – Republicans have been improving in Pittsburgh, its substantial black population limits their potential.

The puzzling thing, however, is why Appalachian working-class whites are moving so rapidly right. It cannot be simply race: both Vice President Al Gore and Senator John Kerry were white, after all, yet they still did progressively worse. It cannot be simply elitism, either: Governor Mike Dukakis and Governor Adlai Stevenson were intellectual technocrats, yet they won what Mr. Kerry and Mr. Gore could not.

Finally, it is not as if all the white working-class has suddenly turned Republican: voters in Michigan, northeast Ohio, upstate New York, and Silver Bow and Deer Lodge Montana, amongst other regions, still retain the Democratic habit. In Pennsylvania, working-class strongholds such as Scranton and Erie, surrounded by a sea of Republican counties, also continue to vote deep blue. They will be the topics of the next post.

–Inoljt, http://mypolitikal.com/