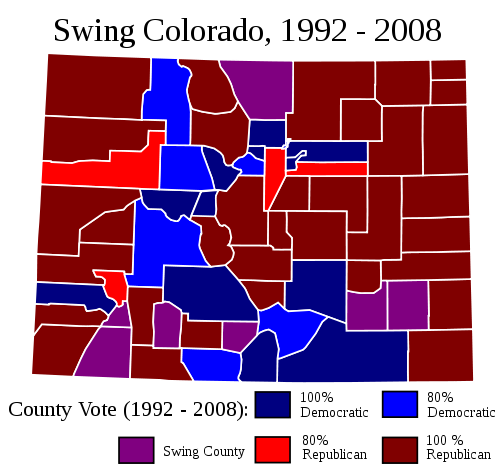

This is the fourth part of a series of posts analyzing the swing state Colorado. It will focus on the complex territory that constitutes the Democratic base in Colorado. The last part can be found here.

Democratic Colorado

In American politics, the Democratic base is almost always more complex than the Republican base, a fact which is largely due to complex historical factors. Democrats wield a large and heterogeneous coalition – one which often splinters based on one difference or another. The Republican base is more cohesive.

The same is true for Colorado. Republican Colorado generally consists of rural white Colorado and parts of suburban white Colorado. Democratic Colorado is more difficult to characterize.

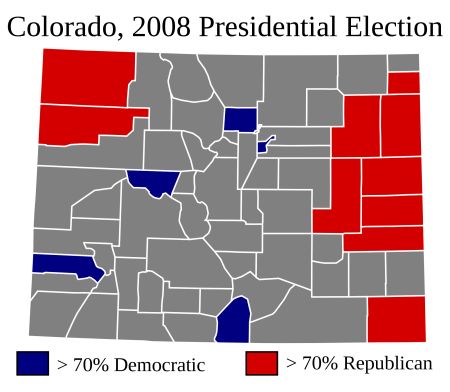

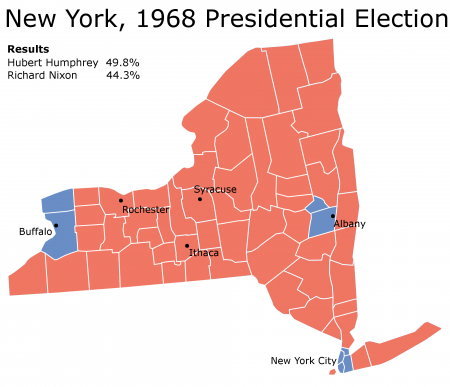

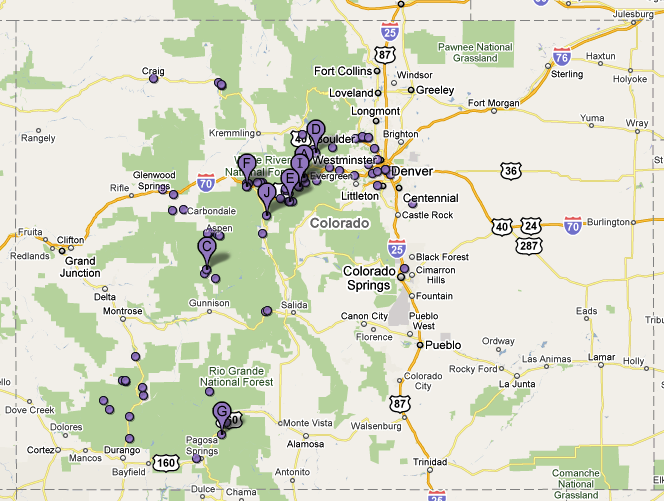

A look into President Barack Obama’s strongest counties provides some insight:

More below.

The Republican counties pictured here are fairly similar: they are thinly populated, homogeneously white rural counties. The Democratic counties, on the other hand, are quite different. There are four facets to Colorado’s Democratic base, and each facet is represented in the picture above.

Denver and Boulder

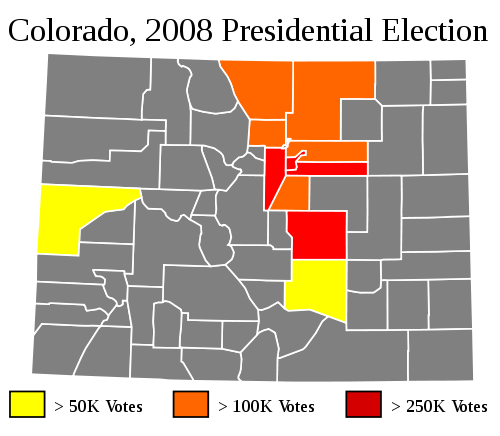

As the post focusing on the Republican base explained, the red-colored counties above constituted 1.2% of the total vote in 2008. A Republican who wins Colorado will win these places, but they are not necessary to win the state.

The same is not true for a Democrat who wins Colorado. The blue-colored counties – or, more specifically, Denver and Boulder – are absolutely essential for a Democratic candidate to win Colorado.

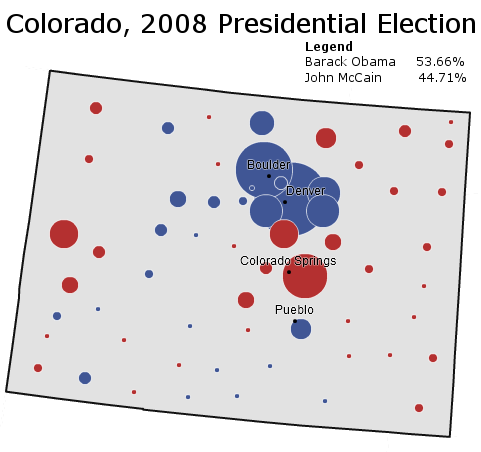

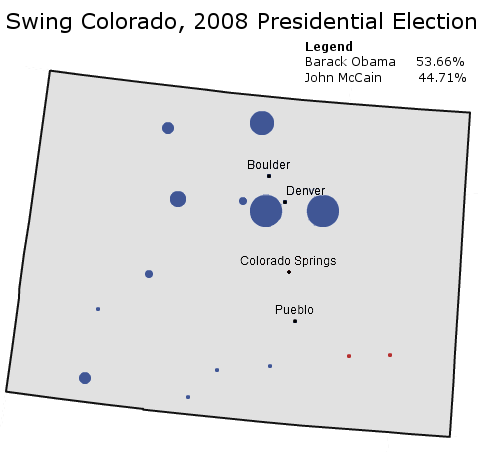

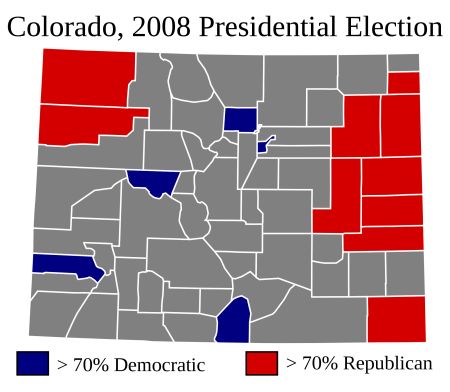

The map below illustrates this fact:

As is evident by the map, Denver County and Boulder County are the two foundations of the Democratic base in Colorado. Mr. Obama gained a margin of 221,570 votes from the two counties. Without the cities of Boulder and Denver, Mr. Obama would have lost Colorado – by around 6,500 votes.

Cities are the mainstay of the Democratic Party in modern-day America, and so it is unsurprising that the Democratic base in Colorado rests upon two cities. Yet not all Democratic cities are alike. Boulder and Denver represent two dramatically different types of cities, both of which vote Democratic.

Boulder is a stronghold of Democratic liberalism; in 2000 it gave Green Party candidate Ralph Nader 11.8% of its vote. Like most liberal places in America (San Francisco, Portland, Seattle, the state of Massachusetts) the median resident of Boulder is richer than the median resident of the United States. Boulder is also more homogeneous than the United States; whites compose something like four out of five people in Boulder County. In this, Boulder is also not much different from most liberal places either.

Denver, in contrast, has more in common with machine-cities like Chicago, Los Angeles, and Detroit. Like these cities, Denver is poorer than the United States. Another commonality is the high number of minorities: Hispanics are more than one-third the total population, non-Hispanic whites less than half. Places like San Francisco and Seattle are more Democratic than liberal; places like Denver are the opposite. On the other hand, in 2000 Mr. Nader also got 5.86% of Denver’s vote – indicating the presence of a substantial liberal bloc.

Electorally, however, these differences do not matter. Both Denver and Boulder vote consistently and powerfully Democratic, and will continue doing so in the foreseeable future.

Rural Democratic Colorado

Colorado and Denver, however, constituted only two of the five blue-colored counties in the first map. The other three are rural, thinly populated, and highly Democratic areas. This may sound strange at first, given the extent of Democratic weakness in rural America. Yet the Democratic parts of rural Colorado have either one of two characteristics.

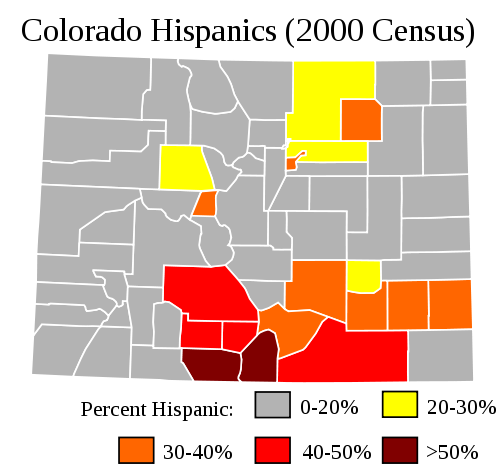

The first characteristic is indicated by the picture below:

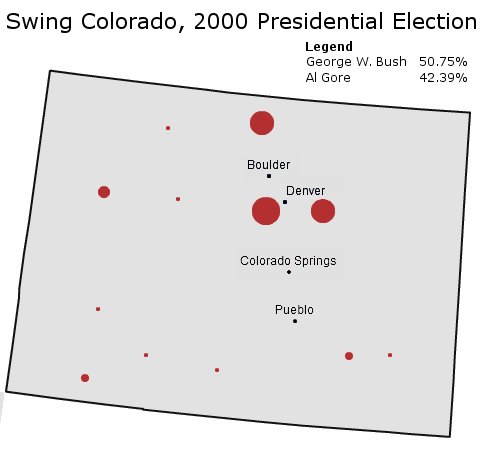

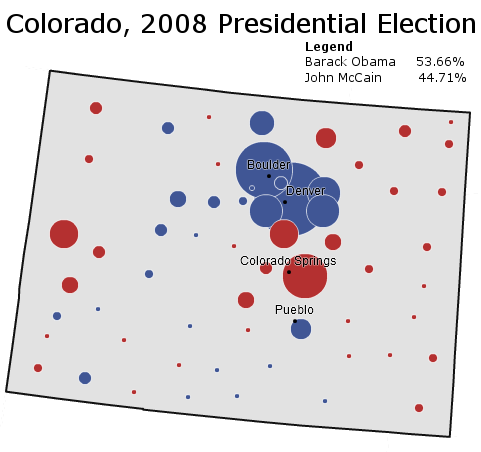

This map uses 2000 Census data to provide a picture of Colorado’s Hispanic population. In 2000 Latinos constituted 17.1% of Colorado; today their numbers have risen to 19.9% of the state population.

Latinos tend to be concentrated in two places: Denver and the areas to its northeast, and a broad band stretching from south-central to south-east Colorado. The latter areas tend to be rural, thinly populated, and the poorest places in Colorado. Due to the high numbers of Latinos, most of these counties usually vote Democratic.

But not all of them. Latinos are not as reliably Democratic as blacks, and they also turn-out in lower numbers. Thus counties with high Latino population correlate with but do not ensure Democratic victory. In 2008, Senator John McCain won seven of the eighteen counties with greater than 20% Latino population. In 2000 Governor George W. Bush actually won Conejos County, where about 58.9% of the population is Latino. Out of the rural counties above, Democrats are only guaranteed victory in the south-central band.

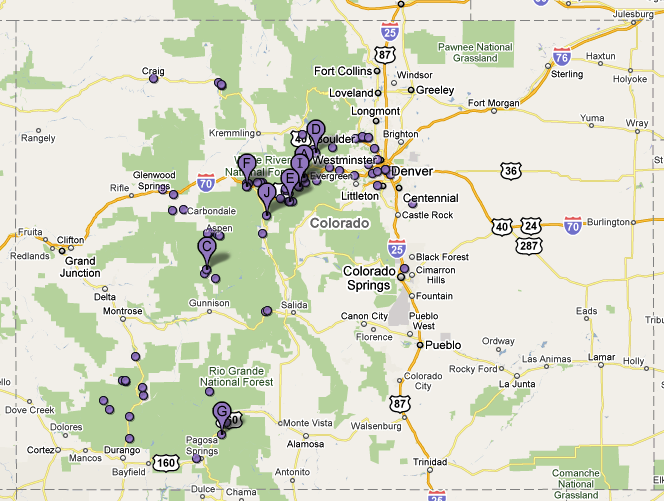

Ski resorts function as another characteristic of rural Democratic Colorado:

For whatever reason, rural counties dominated by ski resorts vote strongly Democratic. These counties are largely located along Colorado’s Front Range. In two of them Mr. Obama won over 70% of the vote: Pitkin County and San Miguel County. Both are home to famous ski resorts: Aspen Mountain in the former and Telluride Ski Resort in the latter.

Ski resort counties are strange places for Democrats to do well in. They are the opposite of the poor Latino counties which also vote Democratic. The people who live in them are generally quite rich, quite famous, and quite white. Rich, 90% non-Hispanic white San Miguel County does not sound at first glance like a Democratic stronghold. Yet when described this way, San Miguel County looks a lot like another Democratic place: Massachusetts.

Conclusion

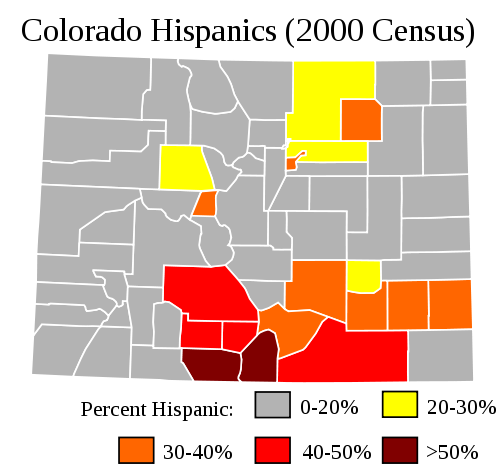

The counties that form the Democratic base form the shape of a “C.” A strong Democratic candidate will expand and fatten the “C.” A strong Republican candidate will cut into the “C” and often split it in two.

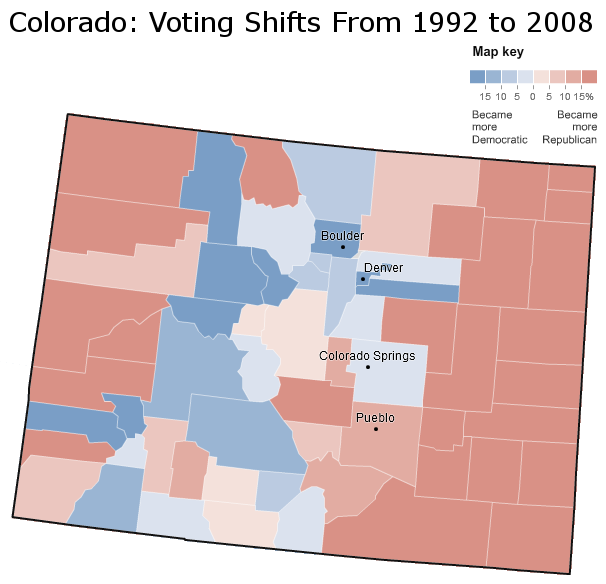

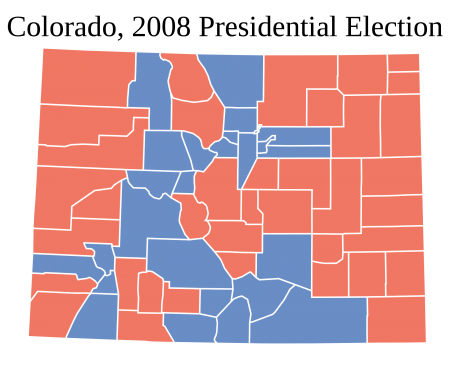

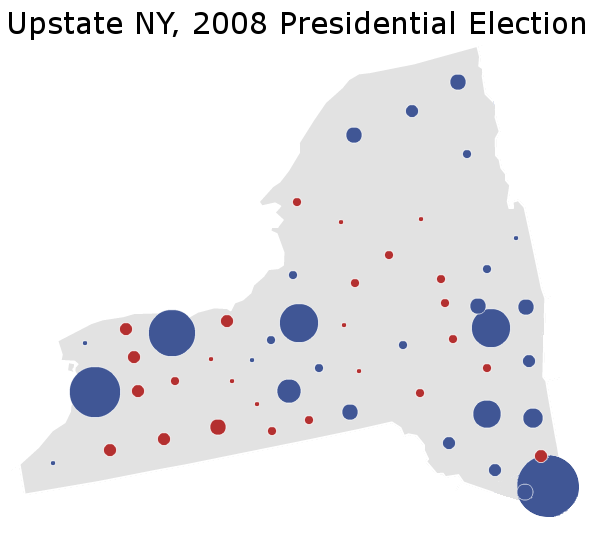

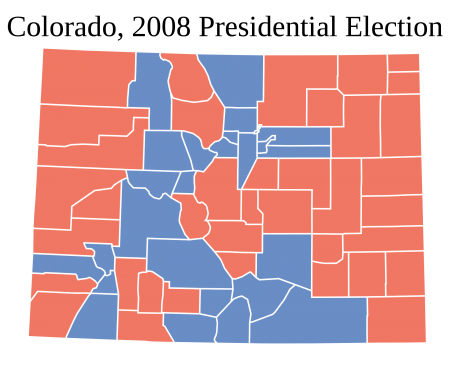

President Barack Obama’s 9.0% victory in Colorado provides one illustration of this Democratic “C”:

In this “C,” all four elements of the Democratic base in Colorado are present. Denver and Boulder form the top part of the “C, which is augmented by suburban Denver counties which Mr. Obama also won. The rural ski resort counties on the Front Range form the left side of the “C,” and the rural Latino counties compose the bottom part.

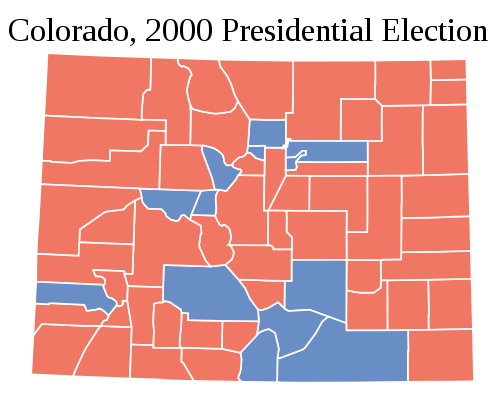

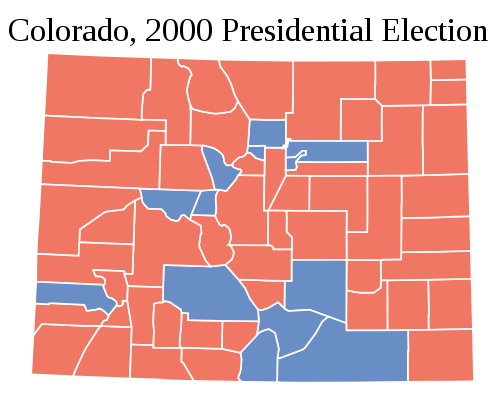

President George W. Bush’s 8.4% victory in 2000, on the other hand, provides an instance of a Republican breaking the Democratic “C”:

Mr. Bush makes inroads everywhere: both rural ski resort counties, rural Latino counties, and the Denver-Boulder metropolis are much more Republican. The Democratic “C” is just present, but barely so.

Unlike other states, therefore, it is relatively easy to tell whether the state is voting for a Democrat or Republican just by looking at a county map. A Democratic victory will look like Mr. Obama’s map. A Republican victory will look like Mr. Bush’s map. This is unlike a state such as New York or Illinois, where Democrats or Republicans can win a 5% victory under the same county map.

(Note: Some maps are edited NYT images.)

–Inoljt, http://mypolitikal.com/